After more than 1,300 years of existence, traffic and pollution were overwhelming the ancient city of Ghent. So in 1997, the second-largest municipality in Belgium did something drastic: It banned cars from an 85-acre area at its city center.

The move met significant initial opposition—to the point that the mayor began wearing a bulletproof vest.

But in the past two decades, the citizenry has come around. A report from the European Commission described the initiative as a “great success,” and Ghent began implementing a plan last April to expand its regulation of transportation even further.

With its commitment to pedestrians and cyclists—and to a cleaner, more sustainable way of living— Ghent presents one vision of what the city of the 21st century could be. To various degrees and with varying amounts of success, other locales around the world are following suit. From San Francisco to Madrid, from London to Mexico City, a movement is afoot to make metropolitan centers less reliant on the automobile and friendlier to other ways of getting around.

And in recent months, an ever-growing group of startups providing novel forms of personal mobility are raising billions of dollars from venture capitalists (VCs) in an effort to take advantage.

Bikes and scooters go boom

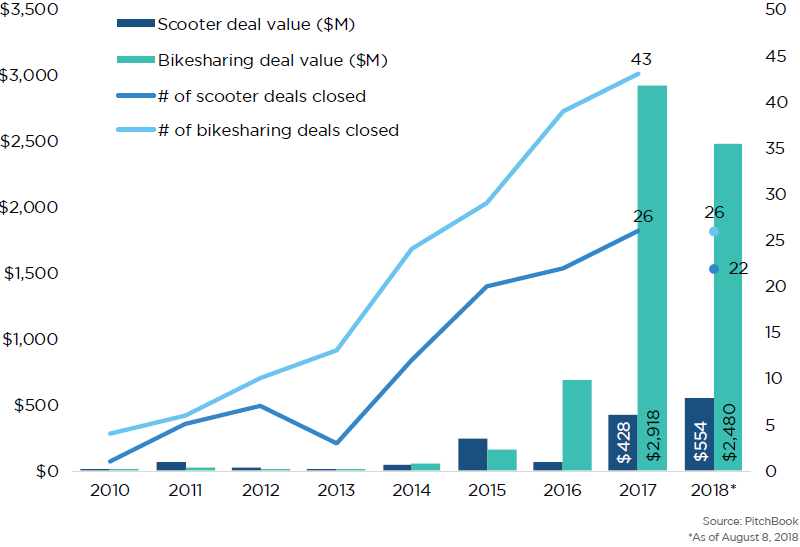

In the past two years, what was at first a minor wave of funding for startups in the bike-rental and electric scooter spaces has turned into a tsunami. Graphs of recent global VC investment in the sectors give new meaning to the phrase “up and to the right.”

The amount of venture dollars going into bikesharing companies like Lime, Ofo, Mobike and Hellobike has increased by at least 172% each of the past five years, per the PitchBook Platform, including a jump of more than 300% each of the past two years. And investment isn’t slowing down in 2018, as the industry’s leaders begin to establish their market positions and expand into an increasing roster of cities.

VC global bikesharing and scooter investment

While there are certainly more players in the bike-rental space, the VC mania is perhaps best encapsulated by the recent funding history of a single scooter startup. That would be Bird, a California-based company launched last year by former Uber executive Travis VanderZanden.

In fewer than 18 months since its launch—and by often deploying the sort of act-first, ask-questions-later philosophy that made Uber infamous—Bird has collected a staggering $418 million in VC funding. Valued at $2 billion in June, it reached a billion-dollar valuation faster than any other current US unicorn. Not bad for a business whose product is still available in fewer than 35 cities.

Most of these companies have similar business models. They use their enormous cash reserves to build up their supply of dockless bikes and/or scooters, then deploy that inventory at a huge scale across busy urban centers. The aim for many is to solve the so-called “last mile” problem, helping travelers complete the final legs of their trips after moving most of the way by car, train or any other method. For either a flat rate— often $1 per ride—or as part of a subscription, users can scan one of the bikes or scooter with their phones and ride to wherever they need to go.

The sprint by venture investors in these spaces mirrors the flood of cash that companies like Uber, Lyft, Grab and Didi Chuxing raised several years ago as the ridehailing industry established itself as an economy-changing force. VCs are enamored with startups aiming to disrupt transportation. And at least one reason for the love affair is clear: Few other industries have the power to so completely change the way the world’s cities operate.

Startups vs. cities

Cities are full of people. Those people need ways to get around. And for millennia, the way they get around has helped shape the way those cities are designed.

One of the Roman Republic’s earliest codes of law regulated the width and upkeep of the city’s growing network of roads, the main method of transport for that era’s carts and animals. Jump forward a couple millennia to London and New York, where the spread of the Underground and the subway system helped drive and organize those cities’ rapid growth. And in the 20th century, Los Angeles and its never-ending sprawl of suburbs are a clear example of a metropolis built for the car.

Bike-rental and scooter-rental services have a long way to go to reach that sort of city-shaping level. It’s quite possible they never will. But in cities like Ghent, the changes to the cityscape are already occurring. In that case, as cars are slowly pushed out of some of the world’s busiest places, bike and scooter startups only need to step into a newly opened vacuum.

In most places, it seems, neither side—the startups nor the cities—wants it to be a battle. But they do have different (and at times competing) motivations.

One of the headline issues from the rise of ridehailing during the previous decade was the way those private startups interacted with cities and other representatives of the public sphere. Take, for instance, Uber and Lyft’s ongoing battle with New York City’s taxi drivers. In August, the Big Apple passed new regulations limiting the number of ridehailing cars allowed on its streets—a potential hindrance to those companies’ ability to generate piles of cash.

Already, bike and scooter companies are facing similar issues.

Earlier this year, after startups like Bird and Lime had already flooded the city’s streets with scooters, San Francisco passed a law regulating their spread. Nashville issued a cease and desist letter to Bird after the company launched there in May. The Seattle City Council passed a new law in July charging bike-rental startups for the right to maintain their fleets there, the sort of regulation that’s caused Chinese companies like Ofo and Mobike to pull out of several major markets in the US. In August, Bird and Lime halted their scooter offerings in Santa Monica—Bird’s hometown— after the city opted not to work with the startups on a test program.

The presence of such test programs in the first place, though, is a sign that several cities are trying to find ways to work with the new crush of personal mobility startups. Denver seized hundreds of illegally parked Bird and Lime scooters when the startups first began operating there in June, but the city has since begun a new pilot program that will allow limited numbers of electric bikes and scooters on its streets. Portland, OR is in the midst of a four-month test run with Bird and fellow scooter startup Skip.

In most places, it seems, neither side—the startups nor the cities—wants it to be a battle. But they do have different (and at times competing) motivations. And then there are the city-dwellers, who just want sidewalks free from the clutter of a hundred technicolor bikes. Much thinking, talking and negotiating remains to be done between the public and private sectors if bike-rental and scooter-rental services are to reach the potential VCs see.

The electric future

By the time such questions are resolved, however, it’s possible many of those VCs will be cashed out. If a recent spate of deals pairing bike and scooter startups with ridehailing giants are any indication, the personal mobility space could be on the brink of serious consolidation.

Earlier this year, Uber acquired electric bike startup JUMP for a reported $200 million, and in July, the ridehailing colossus announced a partnership with Lime to make the startup’s scooters available through the Uber app. A week before Uber’s Lime deal, Lyft acquired Motivate, a major bikeshare operator that operates specially branded bikeshares in several North American cities. And Didi Chuxing (along with co-investor Ant Financial) is reportedly considering a $2 billion takeover of Ofo, the bike-rental company in which Didi’s has been a longtime investor.

Since the start of 2017, VC investors have poured more than $6.3 billion into bike-rental and scooter-rental startups, creating a new herd of unicorns in the process. Now, larger and more powerful companies are taking notice. They’re betting that cities like Ghent will be the model for the 21st century—that the pollution and traffic of the car is on its way out in major metropolitan centers around the globe, and that the era of shared transportation is here.

It’s not a sure bet. Obstacles still stand in their way. But if it pays off, names like Lime and Bird could become the Ford and Chevrolet of the 21st century.